2025 marked a turning point for biodiversity. What was once treated as a long-term environmental concern is now widely recognised as a near-term economic, regulatory, and financial risk.

Biodiversity loss is increasingly framed alongside climate change as a systemic threat, to supply chains, infrastructure, insurance portfolios, and economic stability.

This shift was visible across policy, finance, and corporate reporting. Nature moved from the margins of ESG discussions to the centre of regulatory debate, disclosure frameworks, and global summits.

Yet 2025 also exposed a familiar pattern: ambition rising faster than implementation. The year delivered meaningful breakthroughs, but also delays, political resistance, and unresolved data gaps.

Breakthroughs: finance and global commitments

One of the most significant developments came from the biodiversity process itself.

At the resumed CBD COP16 in Rome, countries agreed to mobilise $200 billion per year for biodiversity by 2030, including $20 billion annually by 2025, rising to $30 billion by 2030 for developing countries. This marked the first time biodiversity finance targets approached the scale of the problem.

The agreement also endorsed new financing tools, including blended finance, biodiversity credits, and debt-for-nature swaps, signalling growing acceptance that private capital must play a central role in closing the nature funding gap.

This ambitious finance target, part of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, is the equivalent of a “Paris Agreement” moment for nature. To achieve it, parties adopted a comprehensive Resource Mobilization Strategy tapping all sources: national budgets, development banks, private capital, philanthropy and innovative mechanisms.

COP16 also operationalised the Cali Fund, a new global biodiversity fund to share benefits from digital genetic resources.

At COP30 in Belém, forests and land use were elevated within the climate agenda. Brazil launched the Tropical Forest Finance Facility initiative, securing over $6 billion in initial pledges, the largest forest-related commitment ever announced at a climate COP.

However, it’s worth noting the gap is still vast, the global biodiversity financing shortfall is estimated around $700 billion per year. The $200 billion per year mobilization target, while a major step, still covers only a portion of what’s needed to truly safeguard nature.

While the numbers still fall short of what scientists estimate is needed, the direction of travel is clear: biodiversity finance is no longer optional or purely philanthropic.

This reinforced a key message of 2025: nature is now viewed as climate infrastructure.

Disclosure goes mainstream: TNFD momentum

If finance set the ambition, disclosure delivered the momentum. In 2025, the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) moved decisively into the mainstream.

By the end of the year, more than 700 organisations across over 50 countries had committed to TNFD-aligned reporting, representing over $22 trillion in assets under management.

(For context, the TNFD had more supporters in its first two years than the TCFD garnered in its first 18 months.)

This rapid uptake reflects growing awareness that nature-related risks, from deforestation to water stress, are financially material. Importantly, most early TNFD adopters are integrating nature and climate reporting, recognising that the two risks are deeply interconnected.

For corporates and financial institutions alike, 2025 was the year biodiversity data shifted from “nice to have” to decision-critical.

Location-based risk screening, supply-chain traceability, and credible monitoring are increasingly expected, not only by investors, but by regulators and insurers.

Policy reality check: progress, delays, and pushback

On the regulatory front, 2025 delivered mixed signals. In Europe, the EU Nature Restoration Law entered the implementation phase, setting legally binding targets to restore degraded ecosystems across land and sea.

It was a landmark achievement, the first law of its kind, but its narrow passage revealed deep political divisions over nature policy.

At the same time, the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) faced further delays.

Enforcement was postponed to 2026 for large companies and 2027 for smaller firms, following intense pressure from industry and concerns over readiness.

While framed as a technical adjustment, the delay exposed a broader challenge: many companies and supply chains remain unprepared for nature-related compliance.

More broadly, 2025 saw rising political tension between environmental ambition and competitiveness.

Calls to “simplify” sustainability regulation gained traction in several regions, raising concerns that nature policy could be weakened just as risks are becoming clearer.

In short, the EU’s flagship anti-deforestation law remains intact, but its enforcement timeline has slipped, revealing tensions between environmental urgency and economic concerns.

The implementation gap

Perhaps the defining theme of 2025 was the gap between global commitments and real-world delivery.

Under the Global Biodiversity Framework, countries were supposed to submit updated National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) ahead of COP16 (originally scheduled for late 2024). In reality, 85% of countries missed that deadline.

Even a year later, only about 28% of parties (55 out of 196) had released their new biodiversity plans, leaving the majority of nations without up-to-date roadmaps for achieving the global targets.

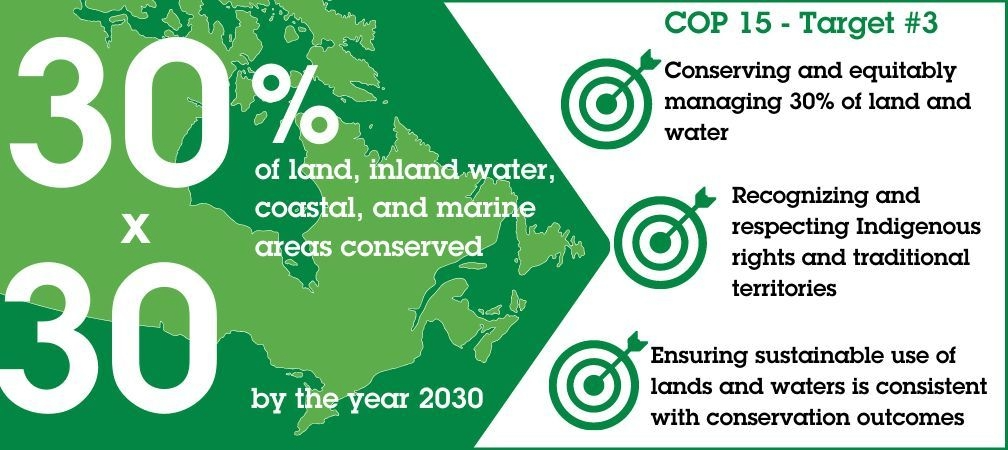

Despite agreement on the “30 by 30” target, protecting 30% of land and sea by 2030, a majority of countries have yet to submit updated national biodiversity plans, and many that have fall short of the agreed ambition.

Finance remains similarly misaligned. While hundreds of billions are now pledged for biodiversity, trillions of dollars continue to flow into nature-negative activities through subsidies, land conversion, and extractive industries.

The challenge is no longer defining what needs to happen, but redirecting capital at scale.

Data gaps compound the problem. Unlike carbon, biodiversity cannot be captured by a single metric. Measurement requires spatially precise, scientifically robust monitoring, an area where many organisations are still at an early stage.

What COP30 means going forward

COP30 did not resolve these challenges, but it clarified the direction of travel. Climate action is increasingly judged on its impact on land, forests, and ecosystems.

There were significant strides: as noted, the Brazil’s Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF) launched with over $6–7 billion pledged, and there was “huge political support for a deforestation roadmap” to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030.

Encouragingly, synergies across the Rio Conventions (Climate, Biodiversity, Desertification) featured prominently for the first time in the negotiations, laying a foundation for deeper integration.

This was evident in the “Belém Joint Statement” issued by the heads of the UNFCCC, CBD and UNCCD during COP30, where they agreed to work together and stressed the need for integrated approaches to tackle climate and biodiversity in tandem.

Such high-level coordination between convention leaders is unprecedented and signals a growing recognition that we must break down the siloed approach to these crises.

The growing alignment between the climate and biodiversity agendas, visible in joint statements, finance initiatives, and adaptation metrics, suggests that future climate policy will be inseparable from nature outcomes.

For businesses and financial institutions, this means biodiversity risk will increasingly shape regulation, insurance underwriting, and access to capital. Nature is no longer a separate ESG pillar; it is becoming a foundational layer of climate credibility.

From awareness to action

2025 was the year biodiversity became unavoidable. Finance scaled up, disclosure accelerated, and policy ambition remained high, but implementation lagged.

The message going into 2026 is clear: the next phase is delivery.

For insurers, investors, and corporates, the priority is moving from commitments to credible, evidence-based action, grounded in robust data, transparent reporting, and location-specific risk understanding. Biodiversity is no longer a future risk.

It is a present one, and those who act early will be better positioned as regulation tightens and scrutiny grows.

The biodiversity decade is underway. The question now is who turns ambition into impact.

.png?width=400&height=250&name=Field%20Notes%20Logo%20(White%20background).png)

-1.jpeg?width=400&height=250&name=Untitled%20(21)-1.jpeg)

.png?width=400&height=250&name=Untitled%20(91).png)