In December 2025, England announced a major change to its Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) regulations: developments under 0.2 hectares (2,000 m²) are now exempt from delivering the mandatory 10% biodiversity uplift. The reform aims to reduce costs and delays for small developments and accelerate housing delivery, particularly for SME builders. But what has actually changed?

What is going to change in 2026?

A new size threshold was introduced: if a development site is smaller than 0.2 hectares (roughly half an acre), it no longer needs to calculate or deliver BNG as part of the planning process.

This exemption, announced by the Housing Secretary on 16 December 2025, forms part of wider national planning reforms. It is due to take effect from April 2026, subject to parliamentary approval of the statutory instrument.

How is this different from before?

Previously, BNG applied to nearly all developments, with only a minimal exemption for proposals affecting less than 25 m² of non-priority habitat.

In practice, this threshold was extremely low, meaning most small schemes still required full BNG compliance. The new rule dramatically raises the bar, exempting sites up to 2,000 m², an 80-fold increase.

Unlike the old rule, which focused on habitat loss, the new exemption is based on total site area. This means even sites with substantial green space may now be exempt if the overall plot remains under 0.2 hectares.

Importantly, BNG still fully applies to all sites above 0.2 hectares, and protections for irreplaceable habitats remain unchanged.

In effect, the policy has narrowed the scope of BNG to remove the smallest sites while preserving its role for larger developments.

Why Announce a 0.2 ha Exemption?

The government introduced the 0.2-hectare BNG exemption to simplify compliance for minor developments.

After BNG became mandatory in late 2023 and early 2024, it became clear that small projects were disproportionately affected.

Minor schemes often had to hire ecologists, run biodiversity assessments, and secure off-site credits for very limited impacts, adding significant cost, delay and complexity for SME developers.

To address this, ministers opted for an area-based exemption, removing BNG requirements from sites below 0.2 ha, roughly equivalent to 5–10 homes, depending on density.

The goal is to reduce regulatory burden, unlock small brownfield and infill sites, and ease pressure on planning authorities.

This compromise followed a 2025 consultation, where options ranged from 0.1 ha to 1 ha. Environmental groups favoured a lower threshold, while developers sought a higher one.

The final 0.2 ha cutoff reflects a middle ground, aiming to support housing delivery without undermining biodiversity outcomes.

Impact on Planning Applications: By the Numbers

Planning Portal data shows that 43.1% of BNG-eligible applications since November 2023 would fall below the new 0.2 ha threshold, 13,601 out of 31,546 schemes.

Yet these account for less than 1% of total land area, equating to no more than 5 of 500 square miles assessed so far. This underpins the government’s argument: many projects affected, but minimal ecological footprint removed.

Looking more broadly, analysis for CIEEM suggests up to 82% of all planning applications could now be exempt, as most schemes are small-scale.

This shift is expected to significantly reduce workloads for local planning authorities, freeing resources to focus on larger, higher-impact developments.

Supporters argue this could also speed up planning decisions for minor projects and help unblock housing delivery.

Putting 0.2 Hectares in Perspective: How Big Is That?

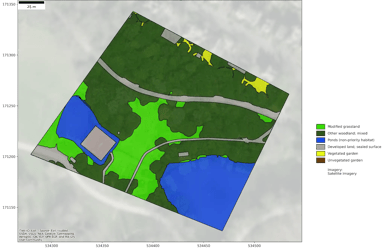

It can be hard to visualise what 0.2 hectares (2,000 m²) actually looks like. Here are a few simple comparisons to bring it to life:

- Around 7–8 tennis courts: A standard doubles court is about 260 m², meaning roughly eight courts fit into 0.2 ha.

- About a quarter of a football pitch: A full-size football field averages 0.7 hectares, so 0.2 ha is roughly one quarter of the playing area.

- Roughly 80 London buses: A double-decker bus covers about 25 m², so it would take around 80 buses parked together to cover 2,000 m².

- Around 20 house footprints: Typical new-build homes occupy 80–100 m², so 0.2 ha could physically fit around 20 building footprints, before allowing for roads, gardens, and spacing.

In everyday terms, 0.2 hectares is almost exactly half an acre, similar in size to a large single house plot, a small community green, a modest school site, or a 60–70 space car park. Under the new rules, developments of roughly this scale, such as a small housing cluster or barn conversion scheme, will no longer trigger mandatory BNG.

How Many Homes Could Be Built on 0.2 ha?

A key aim of the exemption is to unlock small housing sites, so it helps to understand what 0.2 hectares (2,000 m²) can realistically deliver. The answer depends on housing density:

- Suburban density (~30 dwellings/ha): around 6 homes, typical of a small cul-de-sac of detached or semi-detached houses.

- Medium density (~50 dwellings/ha): roughly 10 homes, such as short terraces or compact village schemes.

- Urban density (~100 dwellings/ha): up to 20 flats, likely in a low-rise apartment block.

- High-density city sites (200+ dwellings/ha): 40+ apartments, requiring multi-storey development.

In most villages and town-edge locations, densities are below 50 dwellings per hectare, meaning single-digit housing numbers are typical. This supports the government’s framing of these as “minor developments”, often fewer than 10 homes.

Crucially, the exemption is based on land area, not unit numbers. A developer could build five large houses or fifteen small flats on the same 0.2 ha site and still remain exempt.

This removes a cost burden that previously affected small, high-density schemes, giving developers greater design flexibility.

Importantly, exemption from BNG does not override other environmental protections.

Wildlife legislation and local green-space policies still apply, the change simply removes the need for formal 10% net gain calculations and offsetting.

Reactions from Developers, Planners and Environmental Groups

The 0.2 ha exemption has drawn both praise and concern.

Developers, particularly SMEs, have welcomed the change, saying BNG compliance had become costly and disproportionate for very small sites. Jamie Aherne of Edit Land called it a “practical step” that removes delay and risk, helping small infill schemes become viable again.

Local planning authorities broadly support the simplification. A clear area threshold is easier to administer than complex habitat calculations on tiny plots and should reduce workloads. However, some planners and ecologists worry it may weaken routine biodiversity improvements in small schemes.

Environmental groups and professional bodies remain cautious. Over 140 sector leaders urged restraint, warning that cumulative losses from small sites could undermine nature recovery. CIEEM estimates up to 82% of planning applications may now be exempt, potentially weakening BNG’s overall impact. Concerns also remain about loopholes, such as site-splitting. Oliver Lewis of Joe’s Blooms called the change “a sensible first step,” but stressed the need for strong enforcement.

Overall, the reform is seen as a pragmatic boost for small development, but one that must be carefully monitored to avoid long-term ecological harm.

Benefits and Risks of the New Exemption

Like any policy change, the 0.2 ha exemption brings both advantages and concerns.

Potential Benefits

- Boost for small developers: Removing BNG costs and complexity improves viability for SME builders, helping unlock small housing sites and supporting infill development.

- Faster delivery of brownfield and infill schemes: Previously marginal plots may now proceed without expensive surveys or offsetting, aligning with government aims to accelerate housing supply.

- Administrative efficiency: Local planning authorities can focus resources on larger schemes where environmental impacts are greater, improving speed and consistency in decision-making.

- Minimal initial biodiversity loss: Sub-0.2 ha sites represent less than 1% of BNG land area, meaning most ecological gains remain protected.

- Greater clarity: A simple site-size threshold is easier to apply than complex habitat measurements, reducing disputes and misuse.

Potential Risks

- Cumulative habitat loss: Many small sites can add up, risking gradual erosion of urban green space and ecological connectivity.

- Missed opportunities: Without mandatory BNG, small developments may drop simple enhancements like street trees, gardens, or green roofs.

- Loopholes and gaming: Developers may attempt site-splitting or boundary manipulation to avoid BNG.

- Weaker biodiversity markets: Reduced demand for habitat credits could slow investment in nature recovery projects.

- Perceived unfairness: Small differences in site size could lead to inconsistent obligations between similar schemes.

Overall, the reform may accelerate small-scale development but risks undermining cumulative biodiversity gains. Its success will depend on robust monitoring, enforcement, and local planning leadership.

Before and After: BNG Rules Compared

Before

Most developments in England were required to deliver 10% Biodiversity Net Gain, unless they qualified for exemptions such as:

- De minimis impacts: Habitat loss under 25 m² (or <5 m hedgerow).

- Householder developments (extensions, alterations).

- Self-build and custom-build homes (temporary exemption).

- Zero-biodiversity baseline sites, such as fully paved land.

After April 2024, small sites were fully brought into BNG, making even modest schemes subject to ecological assessment and offsetting.

After

All previous exemptions still apply, plus a new site-size exemption:

Any site below 0.2 hectares (2,000 m²) is now exempt from BNG.

This effectively sidelines the 25 m² rule, as most small sites now qualify automatically. The government has also signalled that older exemptions may be phased out, replaced by this simpler, clearer area-based threshold.

In practice, BNG now applies mainly to sites above 0.2 ha, while the 10% target and assessment process remain unchanged for larger developments.

What Further Changes Are Coming?

Several additional reforms are under consultation:

- Brownfield exemption (up to 2.5 ha): May exempt certain low-value brownfield housing sites.

- Simplified rules for “medium” sites (10–49 homes): A lighter-touch BNG process is being explored.

- Streamlined off-site credits: Easier trading and improved supply of biodiversity units.

- BNG for major infrastructure (NSIPs): From May 2026, highways, rail, and energy projects will be brought fully into BNG.

- Design-led biodiversity: Greater emphasis on built-in nature features such as swift bricks and green corridors

A Balancing Act Between Growth and Nature

The 0.2 ha exemption marks a strategic recalibration, not a rollback. It removes burdens from small developments while keeping 99% of BNG land area protected.

Supporters argue it unlocks housing and reduces friction. Critics fear cumulative biodiversity losses and weakened ecological ambition. The long-term success of this reform will depend on monitoring, enforcement, and ensuring larger sites deliver meaningful gains.

As policymakers attempt to balance housing need with nature recovery, the 0.2 ha rule represents a pivotal test of whether simplification can coexist with environmental leadership.

If you have any questions about BNG exemptions or would like to explore how our services can support your project, get in touch with a team member via the form below:

-1.png?width=400&height=250&name=Untitled%20(60)-1.png)